Professional cycling is very good at telling riders how to arrive, but it is much less certain about how they should leave.

For most of a rider’s racing life, the world is organised around a single objective. Food appears at the right moment. Travel is arranged. Decisions are made elsewhere. The body is monitored, protected, and prioritised. Performance is the only currency that matters, and everything else bends to accommodate it. Then it all stops. There is no ceremony. No gradual unwinding. The structure simply disappears.

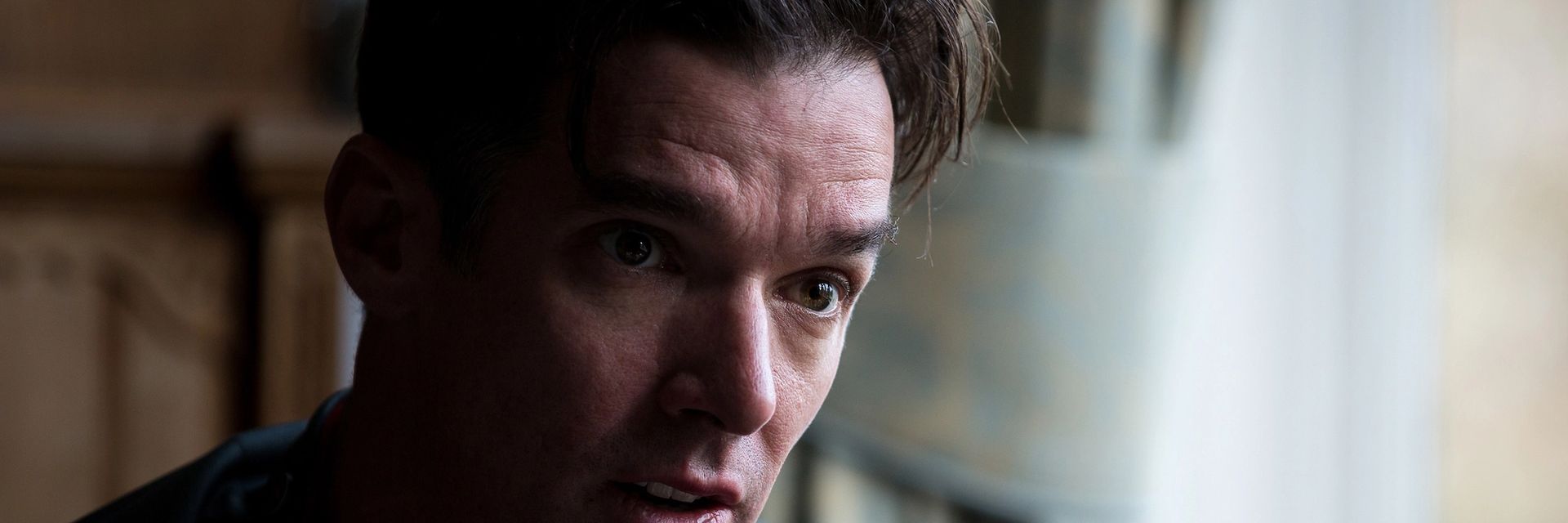

“You’ve been allowed to be selfish,” David Millar tells Velora, in a candid discussion about life after pro cycling. “You’re wrapped in cotton wool and everyone moves for you.”

Millar retired in 2014. As a rider he was a time trial specialist, a Grand Tour stage winner, and one of the defining British figures of his era. Since stepping away he has stayed close to the sport. He's taken on building CHPT3, broadcasting, working with riders, and now taking a senior brand role at Factor Bikes.

From the outside, his post-racing life can look unusually neat. In conversation, he doesn’t present it that way. He has an acute sense of the strangeness of the handover – the speed with which a life built around total structure becomes a life with none at all.

“You come out of it,” he says, “and all of a sudden you’re spinning around the world.”

Image credit: Factor bikes

An artificial world

The difficulty of transitioning out of professional cycling is often framed in financial terms – a drop-off from a six or seven-figure salary, though of course the majority of riders will skew closer to pro cycling’s minimum wage. Millar doesn’t dismiss money as irrelevant. He talks about it as one part of a bigger dislocation.

“The bottom line is it’s an absolute horror show, the transition now,” he says, “because there’s only a tiny percentage that have financial security.”

Professional cycling is a closed environment, typically entered young and exited abruptly. Riders are encouraged to narrow their world around training, recovery and results. Even normal adulthood – routine, relationships, family and broader ambitions – is pushed to the edges.

“You’ve been feted,” Millar says. “The world kind of revolves around you.”

It’s easy, inside that world, to believe the future is something that will sort itself out. The next season arrives quickly. The next contract, the next selection, the next race. It can feel like a long runway, even when it isn’t.

“People say, ‘it’s only ten years,’” Millar says. “‘Just put your head down.’ But you’re not good afterwards.”

The issue is less the years themselves than what those years contain. Riders come out of the sport with a deep skillset in one thing – performance – and very little time spent building anything alongside it. While peers outside cycling accumulate experience, networks, and a professional identity, riders are reducing their lives to a narrow set of repeatable behaviours. That works brilliantly until it doesn’t.

“When you’ve been at the pinnacle and on an ascending spiral since you’re a teenager,” he says, “and then you come out and all of a sudden find that everyone else is kind of hitting their stride and you’re having to go back and start all over again.”

The reset is humbling, he says, and it can be lonely. Even those who stay in cycling often find themselves orbiting it rather than belonging to it in the same way.

“You’re going to have to start from zero again”

Millar says the transition out of the sport has been on his mind for years. He points back to his involvement with the CPA, and to an early sense that cycling had left a gap where support should be.

“I remember when I ran for the president of the CPA, back in 2017,” he says. “One of my biggest mandates was about that: how do we create a better transition?”

He talks about it in practical terms: a pathway, a course, tools that make it clear what is coming. Not soft reassurance, but a realistic understanding that retirement is a restart.

“You’re going to have to start from zero again,” he says. “Which is a pretty humbling experience.”

Millar’s own path after retirement has been public enough to invite easy conclusions. Brand founder. Commentator. Senior industry role. The outline seems so neatly laid out. In reality, it has carried the same uncertainty that many riders experience, only in different forms.

CHPT3, like much of the cycling industry, moved with the violent swell of the COVID-19 boom and the correction that followed. Millar describes an industry that mistook a moment of demand for a permanent shift in culture. Behind that was something else too: an industry that believes in itself very deeply.

“I think one of the biggest problems in the cycling industry is that most of the people who run the businesses within the industry are fans of the sport,” he says. “They are cyclists. They love it.”

He describes that love as a strength, but also a blind spot – a tendency to assume that everyone else will eventually feel the same way, and that the market will expand simply because cycling deserves it.

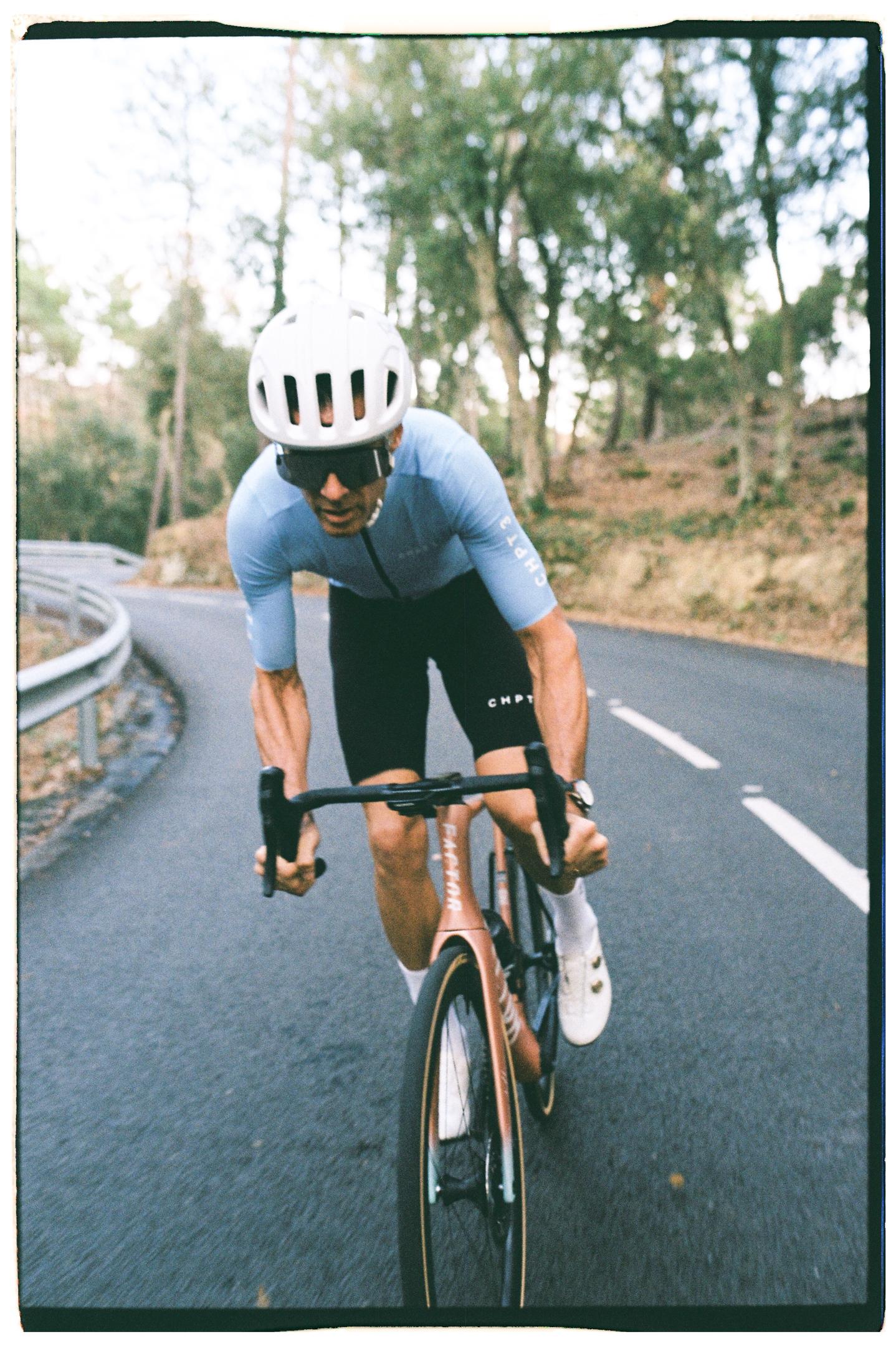

After winding CHPT3 down, Millar moved into a full-time role at Factor, a brand with which CHPT3 already had deep connections. He speaks warmly about the culture there: ex-racers in key roles, a company built around performance machines, a kind of obsessive engineering seriousness that feels familiar to someone who spent his life inside elite sport.

“I’ve rediscovered my love for bikes,” he says. “Actually understanding how they’re made. Geometry. Carbon. All of it.”

It is also, he says, a reminder that these routes are limited. Staying within cycling doesn’t automatically create stability, and leaving it doesn’t automatically create opportunity.

Image credit: Factor bikes

“There aren’t many pathways,” he says. “You don’t really have a skill set that gets your foot in the door somewhere.”

While Millar settles into his new role, he watches the current peloton grappling with pressures that have only intensified since his departure.

A sport transformed

As recent narratives around burnout have proven, cycling has only ramped up in intensity in the last two decades. Last week Simon Yates announced his surprise retirement, and in the wake of that Jonas Vingegaard expressed sympathy and understanding for why a Grand Tour champion would choose to leave in the current climate. Vingegaard regarded it as “a wake-up call for all of us in the cycling world."

Millar describes a sport that has changed beyond recognition since his own era, and he locates the change in familiar places: training, nutrition, data, equipment, and the way riders are supported.

“The fact that you can just actually be fuelled up and the training is so much more refined,” he says. “And I think even with psychological framework around them, I think they are guided, looked after better these days, in terms of the cognitive load, pressure and stress. But then the equipment is just wild now. How fast the bikes are. Nutrition and bikes have lifted it so much.”

He talks about the way knowledge has spread, too. Where once it was closely held by a few teams or a few trusted experts, it now circulates freely.

“There’s now so many,” he says, “It’s almost open-source now, getting incredible training.”

“Before, it was Team Sky breaking ground,” he adds. “You used to be doing loads of carbs in races, et cetera. Now everyone understands that.”

That convergence, in Millar’s view, has leveled the playing field in ways cycling is still adjusting to, not least in terms of credibility, suspicion, and the sport’s long shadow.

“I believe this is cleaner than it’s ever been,” he says. “What’s happened with that as well means that the playing field is levelled… guys who are going for wins consistently are clean.”

It is a claim with substantial weight when coming from someone who served a doping ban earlier in his career and later became a prominent anti-doping voice.

Whether we can pause our cynicism is a difficult question, but there’s no denying that the sport has substantially changed in professionalism and the general development of riders.

What remains oddly underdeveloped is what happens when the racing ends.

“In a few years,” Millar says. “I’d like to kind of find a way to sort of talk more about that. To create a pathway.”

Cover image: Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com